Squalls are a fact of life in most cruising areas, particularly in hot weather. There are basically three concerns with them: rain, wind, and lightning. What do you do when you see a dark sky, or the forecast has a high chance of thunderstorms or squall?

Our first cruising grounds were in the Sea of Cortez, which doesn’t get too many thunderstorms. But the storms that do occur (called chubascos) are doozies. Then we spent a summer in El Salvador with wicked daily thunderstorms. And then we spent ten years in the Florida Keys and Bahamas, also known for squalls and waterspouts.

I can’t remember ever reading an article about what to do when a squall hits when you’re at anchor. They’ve all been about riding one out at sea. But in 17 years of cruising, fewer than a half dozen squalls hit us while underway. Actually, I can only remember 3. But there must have been a few more, so I’ll call it six. At anchor, though? Well over one hundred.

First Steps When a Squall is Forecast

When a thunderstorms is forecast or you see one coming, make sure you’re not anchored in a super-exposed spot. Three times, we’ve been hit by a storm where we had no protection from the direction it came from. And worse, a lee shore behind us.

Once we had too little experience to see the situation developing. The second time we let group think sway us. “They’re not leaving so I guess we’ll be okay.” And the third time an engine problem prevented us from leaving. No question about it: while my first choice is to move to a protected anchorage, I’d much rather be out on open water than in an unprotected anchorage with a lee shore.

The second thing is that we always, always, always anchor like we know it’s going to blow 50. Trust in your anchoring gear and technique gives a lot of peace of mind. Unfortunately, the only way to build up that trust is to go through a few storms. (Details of anchoring like it’ll blow 50).

Before the Squall Hits

Here’s the rest of our plan for dealing with squalls:

If squalls are forecast or you can see them in the area, periodically check radar throughout the day. If in an area with internet and radar stations, you can use a weather or radar app. Put the radar in motion so you can see where the storm cells are headed, how fast they’re moving, and how powerful they may be. In general, the faster the storm is moving, the nastier the wind punch will be. You can also use your boat’s radar and track storm cells just as you would a boat in the distance.

Don’t leave the boat when a storm is approaching! Should your boat drag anchor, you want to be aboard so that you can act if necessary. Our rough rule of thumb is that we don’t leave if we think something will hit in the next hour.

Make sure to set your anchor alarm and turn up the volume.

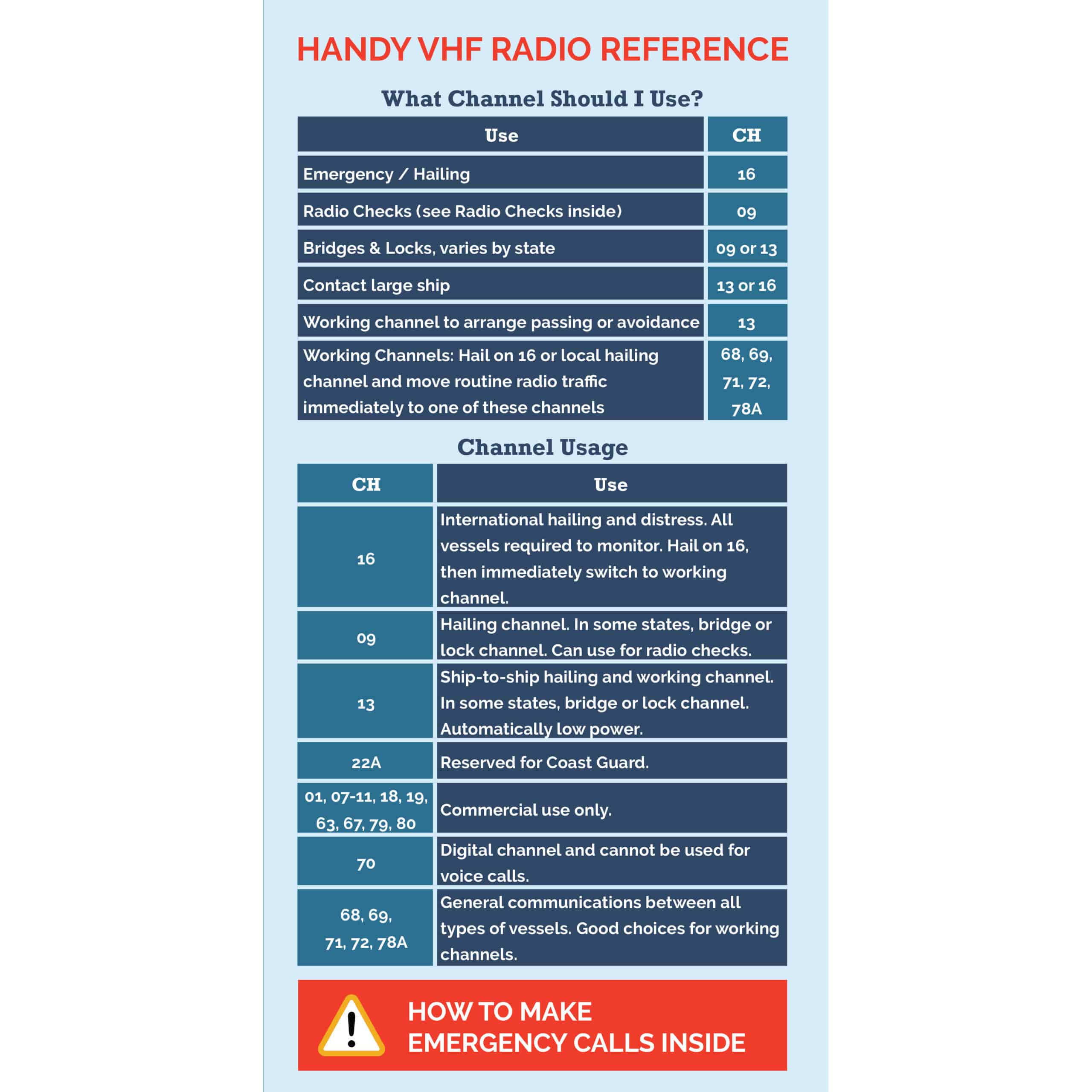

Put your VHF on the local hailing channel and turn up the volume as well.

If possible, hoist the dinghy so that it is more secure. Otherwise, put a second line on it with a bit of slack so that if the primary painter breaks, you don’t lose the dinghy. If hoisted, remove the drain plug so that rainwater won’t collect and possibly break your davits or other lifting device.

Look at your anchor rode and snubber. See if you need to make any adjustments.

Write down the safe course out of the anchorage and tape it beside your helm compass.

If it’s nighttime, have a powerful (hopefully waterproof) spotlight in easy reach of the helm. Also have an air horn in reach.

Bring in anything on deck that could blow away: laundry, gear, toys, cushions. If a sailboat, make sure your sail covers are on and furling sails are in tight and securely tied off.

Take all flags down to avoid undue wear on them. It’ll also be quieter!

Keep foul weather gear where you can quickly grab it from the cockpit.

When the Squall Arrives

As a storm is moving in, take down any windscoops and close the hatches and ports. Put small electronics in the oven and microwave to protect them from lightning (read more here).

Usually, the nastiest wind punch is just as a storm hits so you have to be ready before then. If it looks like the squall will be a bad one, turn the boat’s radar on 10 minutes or more before you expect the storm to hit so that you can “see” even if conditions get nasty. Also turn the engine on if it looks bad, but don’t put it in gear. You just want it ready to pop into gear if needed. Turn your chartplotter and depthsounder on, too – both to monitor your position and in case you must motor out.

As the storm hits, be in the cockpit (with your foul weather gear on!) so that you can see what is happening. Monitor where you are in relation to your anchor – you will fall back on your rode initially but should feel a jerk as you hit the end of it. Use your chartplotter, anchor alarm, and your eyes to make certain that you are staying in the same position. At the same time, watch the boats around you.

If you do drag anchor, and it’s a slow drag with nothing behind you, wait 10 to 15 seconds to see if you stop dragging.

If you’re moving backwards quickly, there’s something close astern, or it’s a prolonged slow drag, you’ll have to go in gear quickly. Motor, raise the anchor, find a safe spot, and re-anchor. Use your “safe heading out” and helm compass if you just can’t see either with your own eyes or radar. It’s rare that you have to resort to this, but you want to be prepared.

If someone has to go forward to raise the anchor, make sure they wear their PFD. And tether them to the boat. In pouring rain, a snorkel mask will make it easier to see.

If another boat is dragging towards you, try motoring to one side or another enough to avoid a collision. And if you’re dragging and can’t motor away from another boat, try to steer enough to miss them – or at least make it a glancing blow.

If you are dragging or you see another boat dragging, alert others by VHF and, if possible, 5 blasts on the air horn. Five blasts on any horn means “danger” or “I need help”.

True squalls generally pass quickly but can dump a lot of rain. If you left the dinghy in the water, check if it needs to be bailed as soon as conditions allow.

Squall Survival

Coming through a squall intact just takes some preparation. And mindfulness. Hopefully with these tips, you’ll come through your next squall at anchor or on a mooring with no damage.

Quickly find anchorages, services, bridges, and more with our topic-focused, easy-to-use waterproof guides. Covering the ICW, Bahamas, Florida, and Chesapeake.

Explore All Guides

Carolyn Shearlock has lived aboard full-time for 17 years, splitting her time between a Tayana 37 monohull and a Gemini 105 catamaran. She’s cruised over 14,000 miles, from Pacific Mexico and Central America to Florida and the Bahamas, gaining firsthand experience with the joys and challenges of life on the water.

Through The Boat Galley, Carolyn has helped thousands of people explore, prepare for, and enjoy life afloat. She shares her expertise as an instructor at Cruisers University, in leading boating publications, and through her bestselling book, The Boat Galley Cookbook. She is passionate about helping others embark on their liveaboard journey—making life on the water simpler, safer, and more enjoyable.

Leave a Reply