Redundancy is defined as “the inclusion of extra components that are not strictly necessary to functioning, in case of failure in other components.”

On a boat, we also refer to them as back-ups. But what I’ve learned in our years of cruising is that there is apparent redundancy and then there’s true redundancy.

Apparent redundancy is having a second system, but with some components in common with the primary system. True redundancy is having nothing in common.

It’s a concept that’s worth thinking about as you plan your spares and think through “what-ifs.”

. . . having a fresh water pressure pump and a foot pump gives you redundant pumps, but not water supply if they both draw from the same water tank or have any hoses in common. A crack in the tank or a leaking hose still means no water.

. . . having a spare diesel engine water pump seems great, but it’s not a lot of help underway or in a remote location if it needs to have a pulley pressed onto it before it can be used. (Yes, we had a spare pump with the idea that we could re-use the pulley . . .)

. . . cooking on the grill seems like a great backup to the stove, but only if they don’t share a propane supply. If they do, and your tank is empty, it’s not going to help. But having two propane tanks won’t help if there is a problem with the stove itself, the regulator or solenoid. So we have a grill that uses the little one-pound propane bottles . . . and also carry a spare 20-pound tank, solenoid, and regulator for the stove.

. . . having two (or more) bilge pumps connected to the same through hull could be a problem if, say, the hose barb broke off it and you had to close the seacock to stop water from pouring back in.

. . . but just having multiple electric bilge pumps isn’t an answer either . . . what happens if the batteries die or are flooded by the water? At the same time, not having any electric pumps means that some will always have to be manning one — what happens when they are exhausted? and how can they fix the problem if they are having to pump?

. . . what about anchoring? In severe conditions, use separate snubbers attached to different cleats or other strong points on the boat. And don’t hook them all into the same point (such as one chain hook) on the rode.

. . . having a backup anchor is great, but keeping it disassembled in the bilge isn’t really going to help if you’ve just lost your primary anchor or it’s not right for the conditions and the boat is dragging. It needs to be ready to go, on its own rode, or it’s not really redundant.

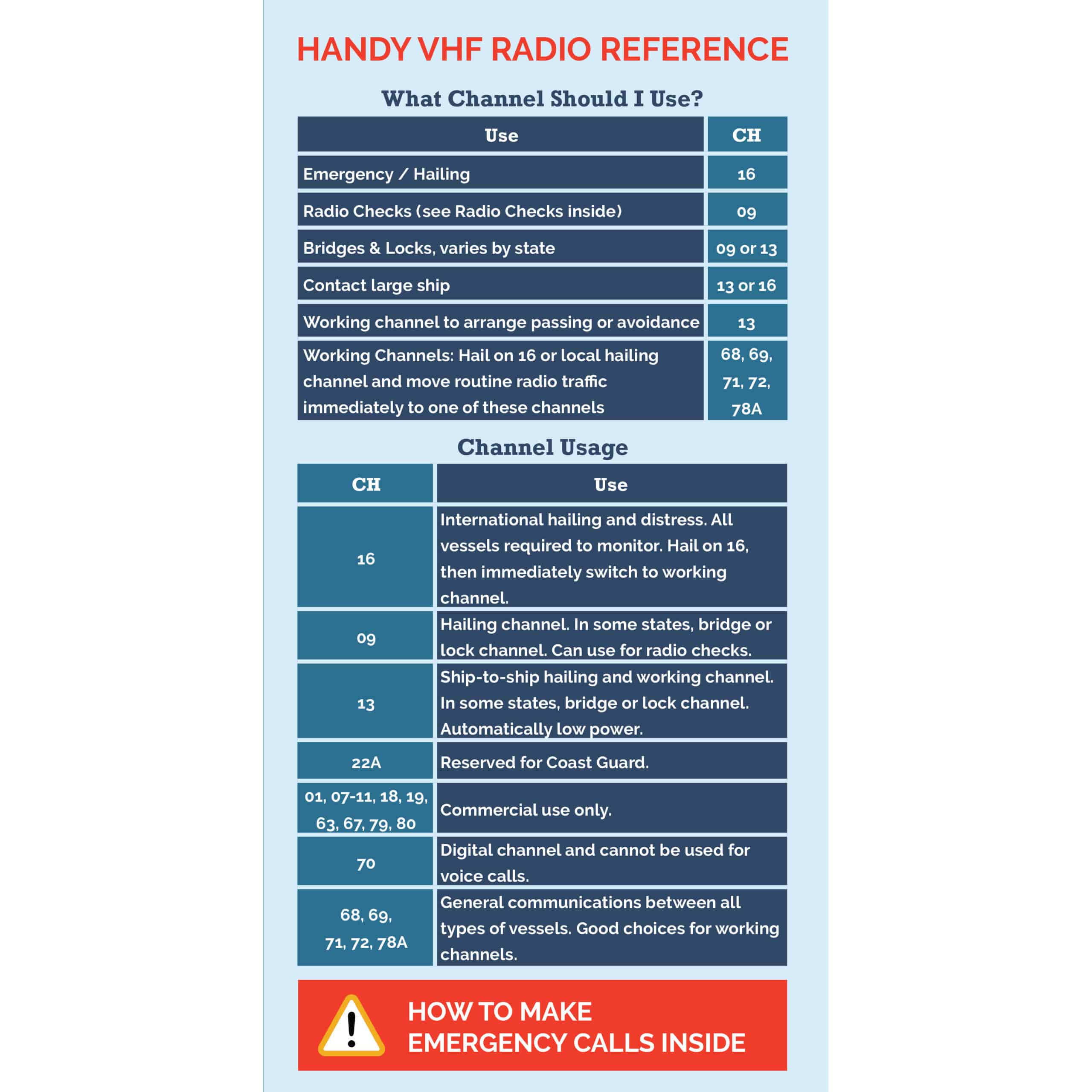

. . . having multiple electronic charting options is great, but if they all get their GPS info from the same antenna, there is no backup if the antenna goes down. Our GPS has its own antenna, as does our VHF/AIS, each of our smartphones, the iPad, and even my laptop. Plus paper charts in case power goes out. Every hour (more often in tricky locations) we write down our lat/long so that we know where we are if we have to switch to the paper charts.

. . . a watermaker is wonderful, but we still keep our tanks topped up every day when we’re away from an easy water source (it’s also better for the pump and membrane to run it every day). If there is a problem with the watermaker, we’d want to start living on reduced rations and making other plans before the tank was empty!

I could go on and on, but you get the idea of examining every system to see where the backup has a point in common with the primary system. Is the backup truly redundant or not?

And that brings up the next point: we can’t have true redundancy in everything. As Dave is fond of saying, “we can’t just tow a whole spare boat with us.”

And so, once we know if we do or don’t have true redundancy in a given system, we have to decide if we need it. For us, that’s a combination of two factors:

- How likely various components are to fail; and

- How catastrophic it would be if a system didn’t work

We’re much more likely to insist on true redundancy for things that could be life-threatening if they failed. I guess a well-stocked life raft is the epitome of true redundancy.

The big thing is to know the choices you’re making. Think through what components you’re assuming won’t fail — and what the consequences would be if they did.

Think about other gear that might suddenly come into play — such as if the refrigerator failed when you were in a remote place and so you switch to using canned meat. What if the can opener breaks? Do you have a spare?

The goal of this whole exercise isn’t to scare you from ever leaving shore. Far from it! The point is to prepare for trips — anything from a weekend out to an ocean voyage — with a framework for making decisions about what gear is needed and what isn’t essential. Everyone’s decisions will be different; there are no universal answers.

If you understand the choices you make — and if they are truly informed choices and not just implicit assumptions — you can leave shore confident in your preparation.

Quickly find anchorages, services, bridges, and more with our topic-focused, easy-to-use waterproof guides. Covering the ICW, Bahamas, Florida, and Chesapeake.

Explore All Guides

Carolyn Shearlock has lived aboard full-time for 17 years, splitting her time between a Tayana 37 monohull and a Gemini 105 catamaran. She’s cruised over 14,000 miles, from Pacific Mexico and Central America to Florida and the Bahamas, gaining firsthand experience with the joys and challenges of life on the water.

Through The Boat Galley, Carolyn has helped thousands of people explore, prepare for, and enjoy life afloat. She shares her expertise as an instructor at Cruisers University, in leading boating publications, and through her bestselling book, The Boat Galley Cookbook. She is passionate about helping others embark on their liveaboard journey—making life on the water simpler, safer, and more enjoyable.

Anonymous says

awesome blog and information!

The Boat Galley says

Thank you so much!

Dave Skolnick (S/V Auspicious) says

Part of planning for spares is stowage. I’ve been on many boats where we had a failure and the owner said “there is a spare in thus and so a locker” only to find the spare was a lump of rust. Vacuum sealing spares with a desiccant is good practice. Take a hard look at your spares list (which goes to Carolyn’s redundancy discussion) and decide if you really need to carry a spare at all or should accept the costs associated with shipping something in.