The morning sun blazed into the v-berth and woke me up. What little sleep I’d had hadn’t come until I reached anchor at 4 am, but I rolled over, as the exhaustion left behind by the long sail from the Bahamas to Haiti lost out to the excitement of seeing in the light of day what, exactly, it was that I had sailed into. Out the companionway and into the cockpit I stumbled, inhaling the smoky air and looking around. The majesty of Haiti’s mountainous skyline was impressive.

My boat, Ave Del Mar, was at anchor in 18 feet of water, comfortably just-close-enough and just-far-enough from the rocky shores of Môle Saint-Nicolas on the west end of Haiti’s northern peninsula. I hadn’t been thrilled with how the anchor felt as it set in the wee hours of the morning, but I had been eager to allow my buddy boater Aldo on Still Free to claim the prime spot close by, a 12 foot patch of sandy perfection where I could now see his Contest 30 pitching gently in the morning breeze.

The residents of Môle Saint-Nicolas seemed busy—motorcycles and the occasional small truck buzzed by on the rough road honking, always honking, and a steady stream of people walked about in every direction carrying baskets, boxes, and fuel jugs. Fishermen worked on their bateau a voile, the ubiquitous and colorful fishing boats that dot Haiti’s waters, repairing sails and stringing nets. Just off the town a group of young boys gathered on a rocky outcropping, staring in my direction and pointing excitedly at the uncommon sight of two sailboats resting in the anchorage. We were the only boats in the waters of Baie du Môle. Absent in addition to other boats were the marinas, beach bars, and dinghy docks that fill most Caribbean anchorages. Clearly this was not where the cruisers go. This was off the common path. This was the real Haiti.

Aldo’s voice pierced the morning calm over the VHF. “John! John! This is Still Free!” came his cheerful, accented voice. This is the only way that Aldo ever hailed me on the radio, and it brought a smile to my face. I answered the call, and Aldo said that he was also up having coffee and gazing at the land around us. “Amazing,” he gushed over the radio. “Ok. We need to make a plan. I will come to you in my dinghy, my friend.”

“Pull & go,” I said. “Pull & go,” he said back, using a phrase that had come to mean “bye-bye” for us. His dinghy’s small outboard had no reverse and no neutral—it was always in gear—and when I asked him one day how he started it he told me, “You pull, and then you go.” It stuck. Cruising is weird sometimes.

Excited, tired, and happy, I went about returning the boat into a livable space, straightening the clutter that always amasses on an overnight run. The sun rose ever-higher in the sky and with it rose those trade winds, whistling in over the mountains to the north. I checked Ave’s orientation to land, taking sights of buildings and trees as the uneasiness about my anchor’s hold on the unknown bottom grew. Sure enough, we were dragging ever so slowly backwards. I quickly fired up the engine and called Aldo on the radio to let him know what was up.

What little I knew about the anchorage I had learned from reading Frank Virgintino’s A Cruising Guide To Haiti, but it seemed possible that I had skipped over the part that says, “If you anchor in front of the town of Môle St. Nicolas… during the early part of the trade wind season… you will find yourself in a lee shore.” Frank was right, and the winds were impressive. My midnight haven was morphing into daytime drama.

With the anchor up and the chartplotter on I started a slow, easy circle that brought us nose into the wind again, hovering over what I hoped was a good spot. Down went the anchor, as I allowed Ave to fall off. No go. That telltale rumbling crept up the chain as the anchor dragged over the sea bed. I hoisted the 45 pound CQR again and motored off, hoping for a bit of luck on my next attempt.

Swinging around again, I noticed a young man ashore yelling towards me and waving his hands frantically. Had I tried to anchor in a spot that blocked the fishing boats? Was I allowed to anchor there at all? Had I read the charts wrong?

Quickly enough the answer came to me—aboard one of those colorful bateau a voiles. Gathering a quick crew of three younger boys, Waving Man had launched his boat, standing proudly at the bow, a smiling Haitian Washington Crossing the Delaware as his young crew rowed him out towards Ave Del Mar. I waited—smiling, wondering, and nervous.

“Your anchor doesn’t work there!” he yelled to me in beautiful English. As the wooden boat drew near his voice softened. “Turn again,” he told me as he stood on the bow and stripped down to his underwear. “I will tell you when to put your anchor down.” He dove off his boat and was soon treading water, watching.

Ave and I made our pass and I scurried forward to drop the anchor when he told me to. As the chain rolled over the bow the young man watched, treading water, instructing me, “More… more…” until eventually he said “Ok! Stop!” I locked the chain onto the gypsy.

Down to my anchor he dove, as gracefully as an Olympian, setting it in the sand. He soon resurfaced, smiling and telling me that everything was now in order. He scrambled back up onto his boat and his crew rowed him alongside Ave Del Mar, tying off loosely to her shrouds. Chatting boat-to-boat, I learned that his name was Kessler and that he had learned English working in Nassau, Bahamas. We chatted and laughed for a half hour or so, and then I thanked him for his help and gave him what I thought was a handsome tip. He smiled. My Haitian experience was off to an exciting start.

I was back below when I heard a voice from outside my boat. “Bonjou! Hallo?” I poked my head out. A young boy, maybe 10, stood in a bois fouille, the wooden dugout canoes so common in Haiti’s seaside ports, grasping onto Ave’s gunwale.

I smiled as he stood in the canoe. “Hello,” I said.

“Bonjou,” he said again in Haitian creole. We looked at each other. It was clear that he spoke no English and equally obvious that I spoke neither French nor Haitian Creole. He pointed to his mouth. “Ongry,” he said, heavily accenting the word hungry. I smiled and set off below to find something I could offer him, reemerging soon with two ginger cookies. The offering felt pitiful to me, two lousy cookies to a hungry young boy, but you can only give what you’ve got, and a partial bag of ginger snaps was the only ready-to-eat thing I could find. He took them from me, nodded in solemn appreciation, and sat, eating them both while holding onto my boat. I tried to smile reassuringly, wishing a little bit that German hadn’t been my chosen second language. A few minutes later we said our good byes—an “Adieu” from me and something in Creole back to me that I didn’t understand other than to appreciate that it was accompanied by a warm smile. The boy rowed the heavy canoe back to shore, where he rejoined his friends on the rocky outcropping.

Excitement ensued. The boys scattered this way and that, finding canoes to row out to Ave for cookies. The progression lasted some time, as boy after boy—and they are always boys in Haitian culture—rowed out, most of them happy with a cookie but some asking for clothing or a dollar. Odd English words crept into their requests here and there, and smiles smoothed over the gaps in our communication. Four particularly-giggly boys without a canoe chose to row out on a long 2-by-10, paddling only with flip flops and bare hands. Every ten or twenty feet one of the boys would slide off of the barely-floating board and into the water where they would resurface to the hysterical teasing of their friends. Eventually they made it, exhausted, wet, and still giggling. They got cookies, too, but also one of my retired dinghy oars. Their trip back to shore was faster than their trip out.

As the procession faded one last boy came out, rowing a yellow plastic sea kayak. As he drew closer I saw that what I had mistaken for a production vessel was, in fact, a homemade kayak constructed from discarded 5 gallon plastic cooking oil containers that had been cut and glued together. His kayak-style oar was a simple tree branch with two small sections of plywood lashed onto the ends. This kid, or someone he knew, was pure genius.

He was the last boy out, which was fortunate because I was literally down to my last cookie. I admired his kayak and did my best to tell him this. “Photo?” he asked. He struck a pose. I grabbed my camera. “Alberto,” he said, pointing to himself.

“John,” I replied, smiling. I snapped a photo and handed Alberto the last cookie. He smiled in thanks but, unlike all the boys before him, he didn’t eat it. With the cookie placed safely between his lips he began the short row back to shore. I watched, curious about the cookie and touched by the sweet nature of this young boy.

I followed his progress through my binoculars as he landed his homemade craft at the base of the rocks that had been so full of gawkers earlier in the day. The perch over the water was empty now save for one other boy about halfway up, who sat chatting animatedly with Alberto as he scaled the rocks with the cookie clenched between his lips. Reaching the spot where the boy waited, Alberto sat down and snapped the cookie in half, handing one piece to his friend and placing the other into his smiling mouth. They sat on those rocks laughing, chatting, and munching on half cookies, childhood buddies side by side looking out over the basin.

I sat back in the cockpit, smiling, too, while I waited for Aldo. Life was very good that day for all of us in Môle Saint-Nicolas, Haiti.

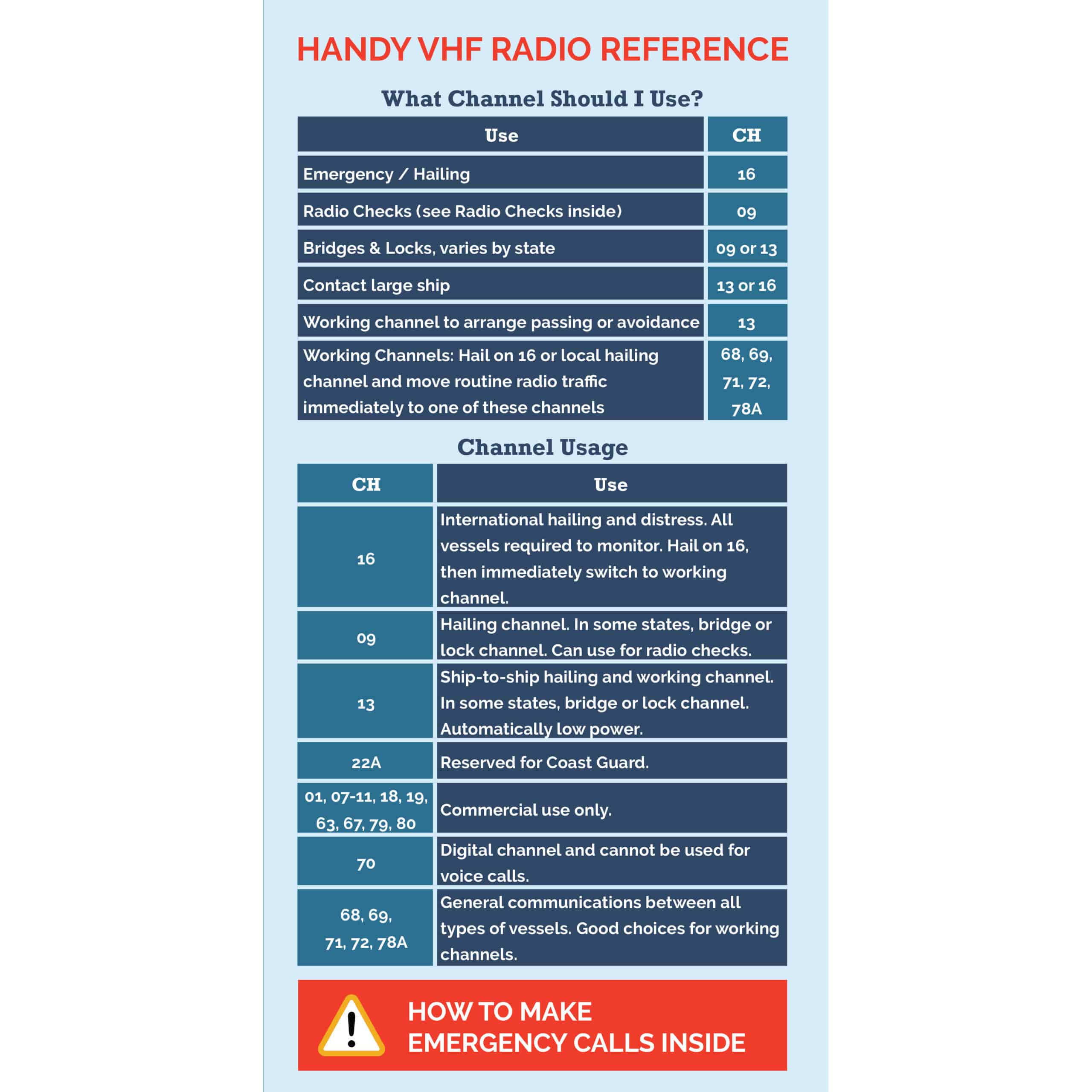

John Herlig is a SpinSheet columnist and a member of The Boat Galley team. He created our VHF Radio Course and also our Handy VHF Reference. John also teaches several courses at Cruiser’s University at the Annapolis Boat Show.

He mostly lives aboard and cruises his 1967 Rawson 30 cutter. He has traveled the East Coast of the US several times, extensively cruised the Bahamas, and sailed much of the Caribbean both on his boat and as delivery crew. Check his tracker to see where he is now. This post originally appeared in SpinSheet magazine.

Quickly find anchorages, services, bridges, and more with our topic-focused, easy-to-use waterproof guides. Covering the ICW, Bahamas, Florida, and Chesapeake.

Explore All Guides

Doc Ford says

Great story. Thank you.